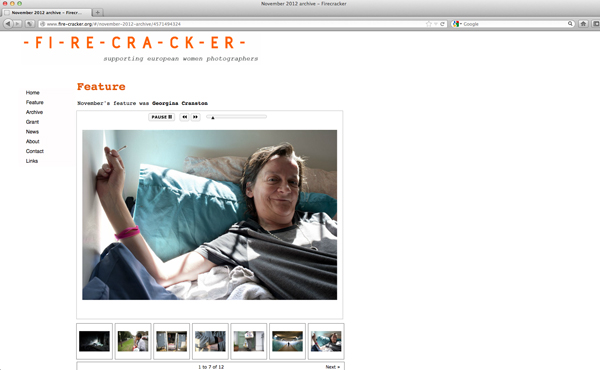

This is Georgina’s story, told in her own words:

(You may find the contents of this story upsetting.)

“I was a really quiet person when I was young, really withdrawn. Now you can’t shut me up. I’ve actually become a little bit madder, but also a lot more confident since being on the street. You have to.

I ran away when I was 18. My dad raped me when I was 14. He was an alcoholic so he doesn’t know he did it. He’s always been an alcoholic because of stuff that happened with his dad. He was always violent if he was drunk. He had knives to mum’s throat, armed police at the door, all sorts.

When my best friend died that was the final straw, my head went. I was like, ‘I’ve got to get away from this place’. I ended up on the streets and I was drinking pretty much from the first day. Alcohol will always be my poison. On the streets you have some of the longest days in the world. If you’re sat shivering in a doorway, just you and your thoughts, it’s either get drunk or take drugs. Or, as I used to, try and end your life.

Now I don’t even want to get indoors – I feel more comfortable sleeping in a doorway than in a bed. It’s like the saying, you can take a man off the streets, but you can’t take the streets off the man. It’s easy living on the streets. I’m quite happy with my life. Being a female makes it harder, but it is OK if you’ve got a good group of friends around you. You don’t have to worry about anything. I’m not very good with stress any more. On the streets, I don’t have anything to lose.

Women are definitely homeless, but they just hide themselves in more discreet places. Not many go to the day centres either. They’re more likely to be in squats because at least they’re behind doors – even if they’re not very good ones. You’ll never really see a single female on the street, because every girl just gets coupled up.

If a girl sees a guy that’s got a place, quite a few will just be like, ‘Oh I’m coupling up with you’. I could never do that, just go into a random stranger’s house.

There’s one person I would trust with my life, and on a daily basis I pretty much do. We met in the day centre of all places. We’re just friends. He would never try to push anything. It’s been an on and off friendship because of moving around, but we kept in touch through Facebook and kept up with all the gossip.

There’s something about London – it’s the easiest place in the world to be homeless. You’ll never go hungry, there’s always a food handout. I had one of my best Christmases this year, spent in the doorway. We had our own Christmas party. There was a really kind person who brought out roast dinners for us. We all managed to get drunk and have a good time and everyone was just really happy.

Something’s always happened to stop me living indoors. That’s just become my way of life. If you’re in a difficult situation you can just walk away. It’s easy because this is not a real world. It’s bizarre, street life. One day I will have to face things. But at the moment I’m happy, so I don’t see the point. If I had my own flat it might be different, but they won’t give me my own flat because of my age.

I can’t commit to anything. Even now I won’t even commit to a city. I’m just wandering all over. I used to love fencing. I was starting to enter competitions and then I left. I went to college to study Law, Economics and Business, but then I got it into my head that I’d rather work with children. My idea was to teach kids how to canoe, kayak, that sort of thing. But since I got a criminal record it’s no chance. I can’t even volunteer with children any more.

I’ve been to prison a few times for assaulting police. When I left prison they put me in a shared house with someone who was doing heroin. After about four or five days, I was like, ‘I’m going back to the streets. Screw this living in a house business’.

I’ve been sectioned twice. They’ve given me psychiatrists, psychologists, counsellors, key workers, everything. And I won’t engage in it properly. In a way I don’t know what to tell them, because I don’t know how to put these sort of things into words. And when they start asking certain questions, I’m just like, ‘How do you think it makes me feel? No, it made me really happy. It put me in a good mood for weeks!’. What do they expect?

I could claim benefits but I choose not to. I’m not doing anything to deserve money. I sit and beg, and that’s someone’s choice to give me money. If it’s coming out of their taxes, then they’re working for me to just do nothing. It’s not really fair. I don’t agree with benefits if you’re not actually needing them. Which I don’t.

I would like to work. I’m thinking of going abroad in March. It’s the start of the picking season. Work for a few weeks and off you go to the next place. I love to explore. My favourite thing is to just walk for hours, and sit and read a book for a while in the middle of nowhere. A lovely person saw me reading the other day and went and brought me back a couple of books. I’m really into my crime and thrillers, but I love all books really.

I’ve never wanted to rely on other people. I’ve never sofa-surfed. I don’t like the feeling of slinging myself on a person. How would they tell me they’ve had enough of me? I don’t want help off the services. They force help on me, they really do. But I’m happy as I am. I have no want to change my life. Which is quite strange…”

(All material on this page is copyright of Georgina Cranston. Text editing by Sarah Carrington.)